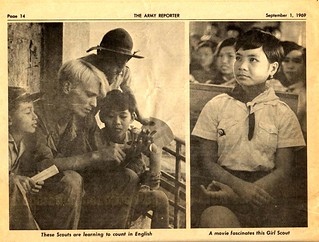

OSS

Deer Team members pose with Viet Minh leaders Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen

Giap during training at Tan Trao in August 1945. Deer Team members

standing, l to r, are Rene Defourneaux, (Ho), Allison Thomas, (Giap),

Henry Prunier and Paul Hoagland, far right. Kneeling, left, are Lawrence

Vogt and Aaron Squires. (Rene Defourneaux)

In the mid-1940s, the Viet Minh, under Ho Chi Minh, looked to the West for help in its independence movement and got it.

As U.S. Army Major Allison Thomas sat down to dinner with Ho Chi Minh

and General Vo Nguyen Giap on September 15, 1945, he had one vexing

question on his mind. Ho had secured power a few weeks earlier, and

Thomas was preparing to leave Hanoi the next day and return stateside,

his mission complete. He and a small team of Americans had been in

French Indochina with Ho and Giap for two months, as part of an Office

of Strategic Services (OSS) mission to train Viet Minh guerrillas and

gather intelligence to use against the Japanese in the waning days of

World War II. But now, after Ho's declaration of independence and

Japan's surrender the previous month, the war in the Pacific was over.

So was the OSS mission in Indochina. At this last dinner with his

gracious hosts, Thomas decided to get right to the heart of it. So many

of the reports he had filed with the OSS touched on Ho's ambiguous

allegiances and intents, and Thomas had had enough. He asked Ho

point-blank: Was he a Communist? Ho replied: "Yes. But we can still be

friends, can't we?"

It was a startling admission. In the mid-1940s, the Viet Minh

leadership, under Ho Chi Minh, looked to the West for help in its

independence movement and got it. As World War II ended, the United

States and its allies, most of them former colonial powers, now

confronted a new problem. Independence movements were emerging all over

the East. But former colonial powers had lost their military muscle, and

the Americans simply wanted to "bring the boys home." During the war,

the United States had sought any and all allies to combat the fascist

powers, only to find, years later, it may have inadvertently given birth

to new world leaders either through misconceptions or missed

opportunities. Vietnam's independence leader, Ho Chi Minh, had been only

a relatively minor figure just a few years earlier. In 1945, Ho became

the leader of a movement that would result in revolutionary tumult for

decades to come.

Deer Team Meets a "Mr. Hoo"

Two months before Thomas' farewell dinner with Ho and Giap, he and

six others from Special Operations Team Number 13, code-named "Deer,"

had parachuted into a jungle camp called Tan Trao, near Hanoi, with

directions to proceed to the headquarters of Ho Chi Minh, whom they

naively knew only as a "Mr. Hoo." Their mission, as they understood it,

was to set up a guerrilla team of 50 to 100 men to attack and interdict

the railroad from Hanoi to Lang Son to prevent the Japanese from going

into China. They were also to find Japanese targets such as military

bases and depots, and send back to OSS agents in China whatever

intelligence they could. And they were to provide weather reports for

air drops and U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) operations on an as-needed

basis.

Thomas had parachuted in on July 16, 1945, part of a three-man

advance team that also included radio operator 1st Sgt. William Zielski

and Pfc Henry Prunier, their interpreter. Not knowing who or what to

expect when they reached the drop zone, Thomas and his team soon found

themselves surrounded by 200 guerrilla fighters who greeted them warmly

and showed them to their huts. They then met with Ho Chi Minh, who

called himself "C.M. Hoo," at his headquarters to coordinate operations

with him. Thomas had no idea that Ho was a Communist, spoke Russian or

had visited the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, Ho openly discussed politics

with Thomas, stressing not only the abuses by the French, but also his

desire to work with the French toward a solution.

In his first official report to OSS Director Archimedes L.A. Patti in

Kunming, China, the following day, Thomas noted, referring to Ho: "He

personally likes many French but most of his soldiers don't." This may

have been one of Ho's ongoing ruses to ingratiate himself with potential

but temporary allies. In his mid-50s, Ho apparently thoroughly

convinced the Deer Team commander of his sincerity. In an effort to

further dispel OSS or U.S. government concerns about Ho, Thomas

emphatically wrote in the report: "Forget the Communist Bogy. VML [Viet

Minh League] is

not Communist. Stands for freedom and reforms from French harshness."

On July 30, the remainder of the Deer Team parachuted in, consisting

of the assistant team leader, Lieutenant René Defourneaux, Staff Sgt.

Lawrence R. Vogt, a weapons instructor, photographer Sergeant Aaron

Squires and a medic, Pfc Paul Hoagland. Defourneaux, a French expatriate

who had become a U.S. citizen, had parachuted into France earlier in

the war to help the Resistance before joining the OSS.

The first person that Defourneaux met when he reached the drop zone

was a "Mr. Van," General Giap, who seemed to be in charge. Ho was not

around much, but when Defourneaux saw him, his first impression was of a

sick old man clearly suffering from some disease. In one of the ironies

of history, the Vietnam War, at least with the Communists under Ho Chi

Minh, might never have happened if the Americans hadn't arrived when

they did.

"Ho was so ill he could not move from the corner of a smoky hut,"

Defourneaux said. Ho didn't seem to have much time to live; Defourneaux

heard it would not be weeks but days. "Our medic thought it might have

been dysentery, dengue fever, hepatitis," he recalled. "While being

treated by Pfc Hoagland, Ho directed his people into the jungle to

search for herbs. Ho shortly recovered, attributing it to his knowledge

of the jungle."

In other reports to the OSS, Thomas had raised a number of political

concerns, from Ho's allegiances, to Indochina's struggle with the

French, Vichy, Japanese, Chinese and the British. In a July 27 report,

Thomas had stated that Ho's league was an amalgamation of all political

parties that stood for liberty with "no political ideas beyond that."

Thomas added, "Ho definitely tabooed the idea that the party was

communistic" since "the peasants didn't know what the word communism or

socialism meant—but they did understand liberty and independence." He

noted that it was impossible for the French to stay, nor were they

welcome since the Vietnamese "hated them worse than the Japs….Ho said he

would welcome a million American soldiers to come in but not any

French."

Control of French Indochina During WWII

French Indochina during World War II was a simmering cauldron of

colonial powers on the decline, of colonial powers divided and other

powers on the rise. Comprised largely of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos,

French Indochina had become in the late 19th century the "jewel in

France's crown" in Southeast Asia.

Among the several competing global, regional and internal interests

in French Indochina during World War II were: Vichy France, which

controlled its colony only with permission of its Japanese ally and

German dominator; followed then by the French Republic, which sought to

reclaim its colonial territories; the United States, which was fighting

against Japan; and Japan, which sought to maintain its regional

hegemony. Also involved were the warring Communists and Nationalists in

China, which sought to influence the region to their south; and a

variety of independence-seeking indigenous factions that all wanted to

remove the yoke of any colonial or imperial power.

Vietnam itself was divided into three main regions with their own

factions fighting for control: the northern Tonkin, central Annam and

southern Cochinchina. French control over Indochina was challenged only

when France fell to the Germans in 1940 and was divided into two

governments—occupied France, and to the south the nominally neutral,

German-dominated Vichy government under World War I hero Marshal Henri

Philippe Pétain. Vichy retained control of most of the French overseas

territories during the war, including Indochina. However, the French

remaining in Indochina were less loyal to the German puppet Vichy

government than they were to Pétain.

As Japan expanded into the Pacific and Asia early in World War II, it

ironically found itself hamstrung by its own alliance with Nazi

Germany. For, so long as both the Vichy government and Imperial Japan

were tied to Germany, the French retained de facto control of Indochina,

although Japan was permitted to establish military bases. As the war in

the Pacific wound down, however, the Allied invasion of Normandy and

liberation of Paris resulted in the fall of Vichy France in August 1944

and, with it, any claims on colonial territories.

Throughout most of World War II, the United States was finding and

supporting allies in China and other Southeast Asian regions, including

French Indochina, to pose a threat to the Japanese military wherever

possible. With the liberation of France in 1944, the U.S. government

turned to its primary coordinator of intelligence during the war: the

OSS, created in 1942 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

OSS to Ho: Work With Us Against the Japanese

At the time, the OSS was operating a base in China's wartime capital,

Chungking. With the growing military complications in Indochina, Brig.

Gen. William Donovan, the director of the OSS, instructed his staff to

use "anyone who will work with us against the Japanese, but do not

become involved in French-Indochinese politics." The Viet Minh, a

liberation movement that had emerged under Ho Chi Minh in the early

1940s, was seeking not only Vietnam's independence from France, but also

freedom from the Japanese occupation. In mid-1944 the OSS approached Ho

to help organize an intelligence network in Indochina to help fight the

Japanese and to help rescue downed American pilots. By then, "Ho had

been cooperating with the Americans in propaganda activities," wrote

Captain Archimedes Patti, head of the OSS base in Kunming, China, and

later Hanoi.

The American association with Ho had actually begun in December 1942

when representatives of the Viet Minh approached the U.S. Embassy in

China for help in securing the release of "an Annamite named Ho Chih-chi

(?) [

sic]" from a Nationalist Chinese prison, where he was being

held for having invalid documents. In September 1943, when Ho was

finally released, he returned to Vietnam to organize Vietnamese seeking

independence. An October 1943 OSS memo proposed that the United States

"use the Annamites…to immobilize large numbers of Japanese troops by

conducting systematic guerrilla warfare in the difficult jungle

country." The missive went on to suggest the OSS's most effective

propaganda line was to "convince the Annamites that this war, if won by

the Allies, will gain their independence."

As the Axis retreated in Europe, and what remained of the Vichy

French government fell, Japan was no longer restrained in Indochina by

its ties to Germany. The Japanese quickly made inroads into Vietnam,

staging a coup d'état in March 1945 that dissolved the French government

and established a puppet government. On March 11, Emperor Bao Dai

proclaimed Vietnam's independence and his intent to cooperate with the

Japanese. Ho Chi Minh was surprised by this development, and regarded

another independence movement as a threat to the Viet Minh's. At the

same time, with the Japanese coup against the French, the OSS realized

it was cut off from the flow of intelligence from French Indochina to

its base in Kunming, and it urged Ho to work with the United States.

"The coup has produced many new and perhaps delicate problems which

will demand considerable attention," the OSS officers in China reported

to headquarters. "The French are no longer in power. There are 24

million [Vietnamese] in Indochina [offering] support for the new

nationalistic regime. Militarily, it calls for an alteration of military

plans; we can't count on French and native troops." The Japanese did

not have the military strength to defend all of Vietnam, however, and

the Viet Minh began to organize themselves as the provisional government

in all but the largest towns, where the Japanese had strongholds.

Also in March 1945, Viet Minh guerrillas

rescued a U.S. pilot who had been shot down in Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh

himself escorted the pilot back to the American forces in Kunming, where

the Fourteenth Air Force was based. Rejecting an offer of a monetary

reward, Ho asked only for the honor of meeting Maj. Gen. Claire

Chennault, founder of China's legendary American Volunteer Group, the

"Flying Tigers," and now commander of the Fourteenth Air Force. During

the meeting on March 29, Chennault thanked Ho, who, after promising to

help any other downed American pilots, requested only an autographed

photo of the general. Ho would later cannily show the picture to other

nationalist Vietnamese factions as proof of his warm relations with—and

implied support from—the Americans. At this time, few knew that Ho

(whose real name was Nguyen Ai Quoc) was a long-time Communist who had

been trained in the Soviet Union. Even the Office of War Information

reportedly was impressed by Ho and his "English, intelligence and

obvious interest in the Allied war effort."

On April 27, Captain Patti met with Ho Chi

Minh to ask him for permission to send an OSS team to work with him and

the Annamites to gather intelligence on the Japanese. "Welcome, my good

friend," said Ho in greeting Patti. He agreed to work with an OSS team

and asked Patti for modern weapons. Ho then set up a training camp in

the jungle, at place he called Tan Trao—the former hamlet of Kimlung and

the new location of Viet Minh headquarters—about 200 kilometers from

Hanoi. There he prepared for the Americans' arrival.

Deer Team Begins Training the Viet Minh

Captain Patti's OSS group, the Deer Team, was established on May 16

and made its way from the United States to the OSS station in Kunming,

where it waited two months for permission to enter French Indochina.

Finally the decision was made for Major Thomas and the team's six other

members to parachute to the Tan Trao training camp in July.

Captain Patti had served with Thomas in North Africa and thought he

"was a fine young officer but understandably unsophisticated in the way

of international power struggles." Thomas became quick friends with Ho

and Giap at Tan Trao, often ignoring the rest of the team. Part of the

team's mission was to indicate targets for the USAAF, but Thomas spent

most of his time with Ho and Giap, and even redirected USAAF targets

against the Japanese based on Ho's recommendations, in direct conflict

with orders he had received from the OSS.

Defourneaux, who had assumed the alias of Raymond Douglas, the son of

a Franco-American mother, to protect him from the locals, had a

different experience with Ho. The leader continually probed Defourneaux

and challenged his cover story, wary of him. Ho told Defourneaux he

hoped the United States would handle Vietnam the way it had the

Philippines. "We deserved the same treatment," said Ho. "You should help

us reach the point of independence. We are self-sufficient."

Defourneaux did not believe that Giap and Ho were "on the same

wavelength," and that Giap was doing things independently. At the time,

he did not know that Giap, or "Mr. Van," another of the OSS's "friends

of the forest," was running an indoctrination school on communism.

As Thomas' friendship with Giap and Ho grew, his relationship with

his own men deteriorated, and Defourneaux became wary of them. Ho, and

especially Giap, had "full control over our leader," said Defourneaux.

In his diary, Defourneaux wrote of Thomas: "I stay with the boys and

cannot help hear their conversations. They hate him, personally I hate

him more and more every day." He said that Thomas thought Ho and Giap

were simply agrarian reformers, "but Ho didn't know how to use a shovel

and Giap didn't know how to milk a cow."

Deer Team members supervise small-arms training at Ho's Tan Trao jungle camp in August 1945. (National Archives)

The

members of the Deer Team had to wait a couple of weeks for supply drops

in early August before they could start small-arms and weapons training

for the guerrilla forces. Once the arms arrived, the Americans showed

the Viet Minh (most were recently civilians) how to fire the American

M-1 rifle and M-1 carbine, and how to use mortars, grenades, bazookas

and machine guns. For training, they used U.S. Army field manuals, and

focused on guerrilla warfare.

Japan Surrenders and Ho Declares Vietnamese Independence

Shortly after training began the second week in August, Sergeant

Zielski, the team's radio operator, picked up a broadcast on August 15

announcing the Japanese surrender, following the atomic bombing of

Hiroshima on August 6, and Nagasaki on the 9th.

Realizing its training mission was over, the Deer Team issued arms to

the soldiers and prepared to leave the following day. Under the terms

of Japan's surrender, the British would occupy the south of Vietnam, and

the Chinese would move to the north to disarm Japanese soldiers and

return them to their homeland.

The Americans left camp on August 16 and traveled on foot with Giap

and his troops to Thai Nguyen, the French provincial capital. There, the

guerrillas fought the French and the Japanese until the French governor

capitulated, on August 25, and the Japanese, finally realizing their

homeland had surrendered, accepted a truce the next day. During this

fighting, Giap had arranged for the Deer Team to stay hidden away in a

safe house on the outskirts of town.

Meanwhile, the Viet Minh had planned to hold a conference in Tan Trao

on August 16, the National People's Congress. About 30 delegates from

Vietnam, Thailand and Laos had assembled in the village to discuss their

concerns. Over the next several days, amid political uncertainty,

several of the delegates had attempted to seize control. Ultimately Ho

Chi Minh claimed leadership and was elected president of the provisional

government on August 27. They proposed and voted on a new national

anthem, and a new national flag with a gold star on a red background,

which would become intimately familiar to most U.S. ground troops two

decades later.

A week later, on September 2, the same day General Douglas MacArthur

received the formal Japanese surrender aboard the battleship

Missouri,

Ho Chi Minh was in Hanoi and declared Vietnamese independence from all

colonial powers, using the American Declaration of Independence as his

template. Banners of "Welcome to the Allies" (specifically, the United

States) flew in the city's Ba Dihn Square, the OSS contingent in Hanoi

photographed the occasion and Minister of the Interior Giap recognized

U.S. support in a speech.

Coincidentally, the same day of Ho's declaration of independence, Lt.

Col. Peter Dewey, the nephew of two-time presidential candidate Thomas

Dewey, arrived in Saigon. The colonel was commander of another OSS team

in Indochina, code-named "Embankment," which was overseeing intelligence

in the Saigon area. As the month wore on in Saigon, the British, free

from hostilities with the Japanese, became politically involved, chaos

ensued and civil war raged. Dewey was ordered out of Vietnam by the

British, who suspected him of working with the Viet Minh. Before

leaving, Dewey wrote in a report to the OSS: "Cochinchina is burning,

the French and British are finished here, and we ought to clear out of

Southeast Asia."

On September 26, two days after the Viet Minh led a national strike

in response to British-imposed martial law, Dewey was ready to depart

Saigon. Leaving in an unmarked jeep for the airport, he was ambushed and

killed a few yards from an OSS house, thus becoming the first American

casualty in Vietnam, nearly two decades before full U.S. involvement in

the Vietnam War. Although there was wide speculation on the shooters,

ranging from conspiracies involving allies to cases of mistaken

identities, an investigation failed to produce an answer. Captain Patti

informed Ho Chi Minh of Dewey's death, and Ho expressed his regrets to

U.S. headquarters in Saigon.

OSS Ends Its Mission in Indochina

With the war in the Pacific over, the OSS ended its mission in

Indochina. The Deer Team had stayed in Thai Nguyen for a few days

following the Viet Minh victory there, "getting fat, getting a sun-tan,

visiting the city and waiting for permission [from Patti] to go to

Hanoi," said Defourneaux. "The Viet Minh did everything to make our stay

as pleasant as possible for us." Once they arrived in Hanoi, the

Americans prepared to return to the United States. The night before

leaving, Major Thomas had his private dinner with Ho and Giap.

In the years that followed, Ho Chi Minh continued to write letters of

a diplomatic nature to President Harry Truman, asking for U.S. aid, but

the letters were never answered. Ho didn't break with the United States

until the Americans gradually became involved with the French in

working against the Vietnamese in the 1950s.

Although OSS agents clearly played a role in Indochina during the

World War II, clear causes and effects with regard to the future

U.S.-Vietnamese conflict are far more cloudy.

First, working with individuals or organizations that did not share

American values or interests was not uncommon, particularly during World

War II. Perhaps the best example was the U.S. alliance with the Soviet

Union, specifically with Josef Stalin.

Second, the United States needed to reach out to an established and

recognized organization within Indochina. There was no natural

indigenous U.S. ally in that region, nor was there an embedded colonial

interest because France itself was divided.

Third, through its

in situ OSS team, the United States had

little immediate effective tactical, operational or strategic impact on

Ho Chi Minh, the future General Giap or the Viet Minh.

Was America, through the OSS, responsible for the rise of Ho Chi Minh

and his subsequent war against the United States? No, but neither was

it completely free of such responsibility. Ho manipulated the

inexperienced leader of the Deer Team as well as U.S. diplomatic

officials in Kunming to serve his unstated needs. Having a personal

photo of Chennault or having OSS agents stand by his side demonstrated

his international standing among the Vietnamese. Also, the failure to

identify Ho Chi Minh as Soviet-trained and a Communist ideologue was a

major American intelligence shortcoming that smoothed the way for Ho's

emergence as a national leader and in the end, an enemy of the United

States.

In later years when asked by journalists or historians about his

relationship with Ho, Thomas was defensive: "I was friendly with him and

why shouldn't I be? After all, we were both there for the same purpose,

fighting the Japanese…it wasn't my job to find out whether he was a

Communist or not."

Ultimately, out of the chaotic and momentous conclusion of World War

II—almost imperceptibly—the die was cast for the coming storm that over

the next three decades would pit the world's greatest superpower against

an indigenous movement led by men who, at its birth, sought the

friendship and support of the United States.

Claude G. Berube teaches at the United States Naval Academy and is the co-author with John Rodgaard of A Call to the Sea: Captain Charles Stewart of the USS Constitution

.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Boundary Representation

is not necessarily authoritative. Names given as 1941 dialect.

International boundaries as of 1941. OSS missions and bases

as of 30 September 1945.

Apart from Detachment 101 in Burma, OSS did not contribute

much to the struggle against Japan until the last year of the war. Early

in the conflict, Army and Navy commanders excluded OSS from their

sectors of the Pacific, thereby forcing Donovan to fight the Japanese in

the only region left open to him, the distant China-Burma-India

Theater. The difficult geography involved and the complicated relations

with America’s British and Chinese allies further delayed OSS’s

deployments. When OSS finally began operating in strength, however, its

operations made an impact on both the Japanese and on the shape of

post-war policies in the region.

OSS had a difficult time winning authority or access to

prosecute operations in China. The Nationalist regime in Chungking was a

government in name only; Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek was more China’s

most powerful warlord than its national leader. He was fighting a war

on two fronts—against the Japanese invaders on one side and against the

Chinese Communists under Mao Zedong on the other. His secret police and

intelligence chief, Tai Li, wanted American aid but had no intention of

allowing Americans to operate independently on Chinese soil. American

efforts to assist Chiang against the Japanese thus had to navigate a

labyrinth of feuds and jealousies in Chungking before any

implementation. Complicating matters still further, Tai Li demanded that

American intelligence operations in China be run—wherever possible—by

the office of Capt. Milton E. Miles, the commander of an unorthodox US

Navy liaison unit.

OSS helped to train and equip Chinese

guerrillas.

Donovan in late 1943 personally told Tai Li that OSS would

operate in China whether he liked it or not, but it still took a measure

of subterfuge for Donovan’s officers to win a role there. The problem

was bigger than Tai Li. At least a dozen American intelligence units

operated in China over the course of the war, all of them competing for

sources, access, and resources. Ironically, Donovan and OSS eventually

“thrived on chaos,” according to historian Maochun Yu. OSS learned to

provide services to American commanders that neither the Chinese nor

other US organizations could match. Access and authorization followed in

due course as OSS analysts and operatives proved that their methods

materially assisted combat operations against the Japanese. For example,

Gen. Claire L. Chennault, creator of the famous “Flying Tigers” and

chief of US air power in China, needed accurate target intelligence. OSS

filled his need through an “Air and Ground Forces Resources Technical

Staff” (AGFRTS), and used this toe-hold to expand well beyond support

for Chennault’s squadrons at Kunming. When a new theater commander, Lt.

Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, began cleaning house and asserting his

authority over all US intelligence operations in China, OSS allied

itself with him and transferred AGFRTS from 14th Air Force to theater

headquarters.

Although it never attained Donovan’s goal of full independence

in China, OSS was a key player in operations and analysis there by the

war’s end. On 9 August 1945—the day that Nagasaki was destroyed by an

atomic bomb—Maj. Paul Cyr, leading a team of Chinese guerrillas on

“Mission Hound,” dropped a strategic railroad bridge across the Yellow

River near Kaifeng. Two spans of the bridge collapsed just as a Japanese

troop train was crossing it. As soon as Japan capitulated, additional

OSS teams ran “mercy missions” in Japanese-held territory to locate and

evacuate Allied prisoners captured early in the war.

Maj. Paul Cyr and Team Hound in training (courtesy of Robert Viau).

Maj. Paul Cyr and Team Hound in training (courtesy of Robert Viau).

OSS plans and activities in China sparked inter-office

arguments over US policy. China’s seemingly intractable troubles and the

vast suffering of its people long confounded American policymakers. OSS

officers who came aboard as China experts or sympathized with the

Chinese people while serving there inevitably drew their own conclusions

about the course of American diplomacy. Opinions in OSS ranged across

the political spectrum, from admirers of Chiang in his struggles against

Japanese invaders and Communist insurgents, to unabashed advocates of

Communist leader Mao Zedong and his promise of justice for the peasantry

through social revolution. Most OSS officers adhered to positions

between these two poles, concerned about the dangers of Chinese

Communism, but frustrated at the corruption of Chiang’s regime and its

reluctance to make reforms to increase the effectiveness of American aid

and to broaden its popular base.

Detachment 404 officers in Jessore, India, planning a supply drop, June 1945.

OSS officers in Thailand faced a different set of policy issues

and demonstrated a high degree of teamwork in tackling them. Thailand

had actually declared war on the United States and Great Britain after

Pearl Harbor and was host to several Japanese bases. Washington had

ignored Bangkok’s declaration, however, when it became clear that a

portion of the Thai ruling elite quietly opposed Japan and hoped to keep

their nation from being drawn more deeply into the conflict. For the

rest of the war the British, Americans, and Japanese danced a

complicated minuet around the possibility that the Thai opposition would

rise against Japan and force Tokyo to divert badly needed combat troops

to subjugating the country. Since the United States had no embassy in

Bangkok, OSS officers eventually found themselves in the unlikely role

of diplomats under the very noses of the Japanese troops guarding the

city.

OSS efforts to contact the rumored Thai underground movement

did not bear fruit until late 1944, after moderate opposition leaders in

Bangkok ousted the dictatorship that had declared war on the Allies.

Thai students recruited and trained by OSS (the “Free Thai”) and the

British SOE were able to meet with underground leaders and even to

broadcast reports from secret locations. Encouraged by the sudden surge

of reporting, General Donovan in January 1945 dispatched two OSS majors,

Richard Greenlee and John Wester, on a mission to Bangkok. Hiding in a

spare palace by day and working by night, Greenlee and Wester confirmed

that the Thai underground was secretly led by the de facto head of

state, Prince Regent Pridi Phanomyong (codenamed Ruth). Pridi and his

followers provided intelligence on the Japanese and offered to rise up

in revolt, but they needed arms and training which only SOE and OSS

could provide. To complicate matters, Pridi and the Free Thai (as well

as OSS observers) suspected that the British harbored imperial designs

on Thailand. If Americans could build a Thai guerrilla force, OSS men on

the scene believed, the Thais could harass the Japanese and bolster a

postwar claim to independence from British tutelage.

OSS officers promised American help for the projected Thai

guerrillas. Back in Washington, the Department of State retroactively

endorsed this commitment, which amounted to a change in US policy. In

Bangkok, Greenlee, Wester, and their successors shuttled to meetings

with Pridi and SOE in curtained limousines driven past the Japanese, who

doubled their garrison in the country but dared not tear up the paper

alliance between Thailand and Japan. The war ended in August 1945 before

actual fighting broke out, but the diplomatic maneuvering continued.

OSS officers close to the Thai peace delegation kept Washington informed

of the course of Anglo-Thai peace talks and assisted American diplomats

in advocating a settlement that ultimately helped ensure Thai

independence.

A Royal Air Force Dakota supporting operations in Thailand had to be unstuck the old-fashioned way at a secret air strip in June 1945.

In China and Thailand, OSS graduated from a reporter of events

to a shaper of American foreign policy. In China, OSS demonstrated that

an American intelligence service aiding a foreign government against

internal enemies could not remain aloof from the exhausting policy

debates in Washington over the wisdom and means of backing the incumbent

regime. By contrast, OSS officers in Thailand showed how much could be

done through clandestine means to help a popular movement struggling

against foreign domination.

Both lessons would echo in the Cold War, especially when the

United States became embroiled in the Vietnam War. Even there, the OSS

left a small but significant legacy for US foreign policy. Against the

wishes of America’s French and Chinese allies, OSS “Mission DEER” had

briefly aided Communist insurgent leader Ho Chi Minh in his fight

against the Japanese in northern Indochina. Other OSS officers, such as

Maj. Aaron Bank, arrived in Laos and in southern Vietnam as the war

ended, and tried to make sense of the bewildering and violent

nationalist and colonial rivalries among the French and Vietnamese

factions there. OSS’s Col. Peter Dewey in Saigon tragically became the

first American killed in Indochina when his jeep was ambushed by

Communist guerrillas (apparently in a case of mistaken identity) in

September 1945.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét