WIKIPEDIA không còn đáng tin cậy nữa vì đã bị CSVN tẩy rửa. Những website dưới đây mới là sụ thực:

http://www.historynet.com/tet-what-really-happened-at-hue.htm

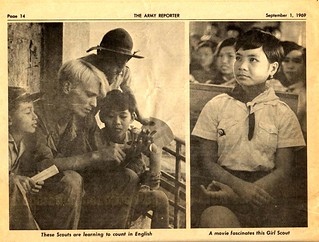

As

the Communist struggled to maintain control of Hue, the longest,

bloodiest battle of the Tet Offensive, fierce house-to-house fighting

left some 116,000 civilians homeless. In the months after the battle,

nearly 2,800 civilian bodies were discovered in 18 hastily concealed

mass graves. (Defense Dept. photo)

Viet Cong intelligence officers prepared a list of

‘cruel tyrants and reactionary elements’ to be rounded up in Hue during

the early hours of the attack.

As dawn broke on the holiday morning of January 31, 1968, nearly

everyone in the old walled city of Hue could see it. The gold-starred,

blue-and-red National Liberation Front banner was flying atop the

historic 120-foot-high Citadel flag tower. When the residents of the

elegant former capital city had gone to bed just hours earlier on the

eve of Tet, they were filled with anticipation for the festivities and

celebrations to come. But now, a shroud of fear and foreboding descended

upon them as they found themselves swept up in war. Seemingly in a

flash, the Communists were now in charge of Hue.Of course, months of meticulous planning and training had made this moment possible. The Communists had carefully selected the time for the attack. Because of Tet, they knew the city’s defenders would be at reduced strength, and the typically bad weather of the northeast monsoon season would hamper any allied aerial re-supply operations and impede close air support.

In the days leading up to Tet, hundreds of Viet Cong (VC) had already infiltrated the city by mingling with the throngs of pilgrims pouring into Hue for the holiday. They easily moved their weapons and ammunition into the bustling city, concealed in the vehicles, wagons and trucks carrying the influx of goods, food and wares intended for the days-long festivities. Like clockwork, in the dark, quiet morning hours of January 31, the stealth soldiers unpacked their weapons, donned their uniforms and headed to their designated positions across Hue in preparation for linking up with crack People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and VC assault troops closing in on the city. Infiltrators assembled at the Citadel gates ready to lead their comrades to strike key targets.

At 3:40 a.m., a rocket and mortar barrage from the mountains to the west signaled the assault troops to launch their attack. By daybreak, the lightning strike was over and the invaders began to unleash a harsh new reality over the stunned city. As PAVN and VC troops roamed freely to consolidate their gains, political officers set about rounding up South Vietnamese and foreigners unfortunate enough to be on their “special lists.” Marching up and down the Citadel’s narrow streets, the cadre called out the names on their lists over loudspeakers, ordering them to report to a local school. Those not reporting voluntarily would be hunted down.

What became of those rounded up would not be readily apparent until long after the battle ended. Even then, as with so much in Vietnam, the facts surrounding their fate would be the subject of often angry and anguished debate among Americans, mirroring the chasm of distrust cleaved by the war and shaded by ideological rigidity, a debate that endures four decades later.

The action unfolding at Hue on the morning of January 31 was just part of a ferocious coordinated attack that was stunning in its scope and execution. An estimated 80,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops simultaneously struck three-quarters of South Vietnam’s provincial capitals and most of its major cities. They achieved nearly total surprise in most objective areas, as they did in Hue, where the longest and bloodiest battle of the Tet Offensive was just getting started.

One of the most venerated places in Vietnam, Hue’s population of 140,000 in 1968 made it South Vietnam’s third largest city. In reality, Hue is two cities divided by the Song Huong, or River of Perfume, with two-thirds of the city’s population living north of the river within the walls of the old city, known as the Citadel. Once the home of the Annamese emperors who had ruled the central portion of present-day Vietnam, the three-square-mile Citadel is surrounded by walls rising to 30 feet and up to 40 feet thick, which form a square about a mile and a half long on each side. The three walls not bordering the Perfume River are encircled by a zigzag moat that is 90 feet wide at many points and up to 12 feet deep.

Inside the Citadel are block after block of row houses, apartment buildings, villas, shops, parks and an all-weather airstrip. Tucked within the old walled city is yet another fortified enclave, the Imperial Palace, where the emperors held court until the French took control of Vietnam in 1883. Situated at the south end of the Citadel, the palace is essentially a square with 20-foot-high, 2,300-foot-long walls. As an observer once put it, the Citadel was a “camera-toting tourist’s dream,” but in February 1968 it would prove to be “a rifle-toting infantryman’s nightmare.”

South of the Perfume River and linked to the Citadel by the Nguyen Hoang Bridge is the modern part of Hue, which had about half the footprint of the Citadel and in which resided about a third of the city’s population in 1968. Here was the city’s hospital, the provincial prison, the Catholic cathedral, the U.S. Consulate, Hue University and the newer residential districts.

As Vietnam’s traditional cultural and intellectual center, Hue had been treated almost as an open city by the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese and thus was spared much of the war’s death and destruction. The only military presence in the city was the fortified Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) 1st Infantry Division headquarters at the northwest corner of the Citadel. The only combat element in the city was the division’s reconnaissance company, the elite Hac Bao Company, known as the “Black Panthers.” The rest of the division’s subordinate units were arrayed outside the city. Maintaining security inside Hue was primarily the responsibility of the National Police.

The only U.S. military presence in Hue on January 31 was the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) compound located about a block and a half south of the Nguyen Hoang Bridge on the eastern edge of the modern sector. The compound housed about 200 U.S. Army, Marine Corps and Australian officers and men who served as advisers to the 1st ARVN Division. The nearest U.S. combat forces were at the Phu Bai Marine base eight miles south down Route 1, home of Task Force X-Ray, a forward headquarters of the 1st Marine Division that was made up of two Marine regimental headquarters and three Marine battalions.

Communist forces in the Hue region numbered 8,000, a total of 10 battalions, including two PAVN regiments of three battalions and one battalion each. These were highly trained North Vietnamese regular units. Six Viet Cong main force battalions, including the 12th and Hue City Sapper Battalions, joined the PAVN units.

While very adept at fighting in jungles and rice paddies, the PAVN and VC troops required additional training for fighting in urban areas. While the soldiers trained for the battle ahead, VC intelligence officers prepared a list of “cruel tyrants and reactionary elements” to be rounded up in Hue during the early hours of the attack. On this list were most of the South Vietnamese government officials, military officers and politicians, as well as American civilians and other foreigners. After capturing these individuals, they were to be evacuated to the jungle outside the city where they would be held to account for their crimes against the Vietnamese people.

The PAVN 6th Regiment, with two battalions of infantry and the 12th VC Sapper Battalion, launched the main attack from the southwest, linking up with the VC infiltrators, and speeding across the Perfume River into the Citadel toward the ARVN 1st Division headquarters. The 800th and 802nd battalions of the 6th Regiment rapidly overran most of the Citadel, but Brig. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong, 1st ARVN Division commander, and his staff held the attackers at bay at the division compound.

Meanwhile, the ARVN reconnaissance company managed to hold its position at the eastern end of the airfield until it was ordered to withdraw to the division headquarters to help thicken defenses there. Though the PAVN 802nd Battalion breached the ARVN defenses on several occasions during the pre-dawn hours, its troops were hurled back each time, leaving the 1st Division compound in South Vietnamese hands. By daylight however, the PAVN 6th Regiment held most of the Citadel, including the Imperial Palace.

South of the Perfume River, the situation was little better for the Americans. The PAVN 804th Battalion twice assaulted the MACV compound, but was repelled each time by rapidly assembled defenders armed with individual weapons. The North Vietnamese troops then stormed the compound gates, where a group of Marines manning a bunker held off them for a brief period before being taken out with several B-40 rockets. This action slowed the PAVN attack and gave the Americans and Australians time to organize their defenses. After failing to take the compound in an intense firefight, the Communists tried to reduce it with mortars and automatic weapons from overlooking buildings. The defenders went to ground and called for reinforcements.

While the battle raged around the MACV compound, two Viet Cong battalions took over the Thua Thien Province headquarters, the police station and other government buildings south of the river. At the same time, the PAVN 810th Battalion took up blocking positions on the city’s southern edge to prevent reinforcement from that direction. By dawn, all of the city south of the Perfume River, with the exception of the MACV compound, was controlled by the North Vietnamese 4th Regiment. Thus in very short order, the Communists had seized control of virtually all of Hue.

With only a tenuous hold on his own headquarters compound in the Citadel, General Truong ordered his 3rd Regiment, reinforced with two airborne battalions and an armored cavalry troop, to fight their way into the Citadel from their positions northwest of the city. These forces encountered intense resistance, but by late afternoon reached Truong’s headquarters.

As Truong consolidated his forces, another call for reinforcements went out from the surrounded Americans and Australians in the MACV compound. Responding to III Marine Amphibious Force orders, but not fully aware of the enemy situation in Hue, Brig. Gen. Foster C. “Frosty” LaHue, commander of Task Force X-Ray, dispatched Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (1/1), to move up Route 1 from Phu Bai to relieve the 200 surrounded MACV advisers.

After entering the city, the Marines were pinned down just short of the adviser compound. More Marines from Phu Bai, Golf Company, 2/5, joined up with the original force and together they fought their way to the compound, sustaining 10 killed in the fight. After the link up, the Marines were ordered to cross the river and break through to the ARVN 1st Division headquarters in the Citadel. As they crossed the Nguyen Hoang Bridge, the Marines were driven back by a hail of enemy fire, suffering heavy casualties in the process.

With the 1st ARVN Division fully occupied in the Citadel and the U.S. Marines engaged south of the river, ARVN I Corps commander Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam and Lt. Gen. Robert Cushman, III Marine Expeditionary Force commander, met to discuss how to retake Hue. They decided that ARVN forces would be responsible for clearing the Communist fighters from the Citadel and the rest of Hue north of the river, while Task Force X-Ray would assume responsibility for the southern part of the city.

General LaHue, now fully realizing what his Marines were up against, dispatched Colonel Stanley S. Hughes, 1st Marine Regiment commander, to assume overall control of U.S. forces. The Marines launched a bitter building-by-building, room-to-room battle to eject the Communist forces. Untrained in urban warfare, the Marines had to work out the tactics and techniques on the spot, and their progress was methodical and costly. Ground gained was measured in inches, and every alley, street corner, window and garden was paid for in blood. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

On February 5, H Company, 2/5 Marines, took the Thua Thien Province headquarters, which had served as the command post of the PAVN 4th Regiment, causing the integrity of the North Vietnamese defenses south of the river to begin to falter. Hard fighting continued over the next week, but by February 14, most of the city south of the river was in American hands. Mopping up would take another 12 days as rockets and mortar rounds continued to fall and snipers harassed Marine patrols. The battle for the new city had been costly for the Marines, who sustained 38 dead and 320 wounded. It had been even more costly for the Communists; the bodies of more than 1,000 VC and NVA soldiers were strewn about the city south of the river.

Meanwhile, the battle north of the river had continued to rage. Although additional ARVN forces were inserted, by February 4 their advance had effectively stalled among the houses, alleys and narrow streets along the Citadel wall to the northwest and southwest. The Communists, who had burrowed deeply into the walls and tightly packed buildings, were still in possession of the Imperial Palace and most of the surrounding area and seemed to be getting stronger as reinforcements made their way into the city.

His troops stalled, a frustrated and embarrassed General Truong was forced to appeal to III MAF for help. On February 10, General Cushman directed General LaHue to move a Marine battalion into the Citadel. On February 12, elements of 1/5 Marines made their way across the river on landing craft and entered the Citadel through a breach in the northeast wall. At the same time, two Vietnamese Marine battalions moved into the southwest corner of the Citadel. This buildup of allied forces put intense pressure on the Communist forces, but they stood their ground.

Attacking along the south wall, the Marines took heavy casualties, as the fighting proved even more savage than in the southern part of the city. Backed by airstrikes, naval gunfire and artillery support, the Marines inched ahead, but the enemy fought back desperately. The battle seesawed back and forth until February 17, when the 1/5 Marines had secured its objective, after losing 47 killed and 240 wounded.

Fighting continued for days, but finally, at dawn on February 24, ARVN soldiers pulled down the Viet Cong banner that had flown from the Citadel flag tower for 25 days and hoisted the South Vietnamese flag. On March 2, the longest sustained infantry battle the war had seen to that point was officially declared over. The relief of Hue cost the ARVN 384 killed, 1,800 wounded and 30 missing in action. The U.S. Marines suffered 147 dead and 857 wounded, and the Army lost 74 dead and 507 wounded. Allied claims of Communists killed in the city topped 5,000, and an estimated 3,000 more were killed in the surrounding area in battles with elements of the 1st Cavalry and the 101st Airborne divisions.

The epic battle for Hue left much of the ancient city a pile of rubble as 40 percent of its buildings were destroyed, leaving some 116,000 civilians homeless. Among the population, 5,800 civilians were reported killed or missing.

The fate of many of the missing took time to emerge, but in the months after the battle grisly discoveries were filling in the blanks as some 1,200 civilian bodies were discovered in 18 hastily concealed mass graves. During the first seven months of 1969, a second major group of graves was found. Then, in September, three Communist defectors told 101st Airborne Division intelligence officers that they had witnessed the killing of several hundred people at Da Mai Creek, about 10 miles south of Hue, in February 1968. A search revealed the remains of about 300 people in the creek bed. Finally, in November, a fourth major discovery of bodies was made in the Phu Thu Salt Flats, near the fishing village of Luong Vien, 10 miles east of Hue. All total, nearly 2,800 bodies were recovered from these mass graves.

Initially, the mass graves were not widely reported on in the American media. The press tended not to believe the early reports, since they came from sources they considered discredited. Instead, most reporters tended to concentrate on the bloody fighting and the destruction of the city. As the graves were discovered, however, investigations were launched to get at the facts of the killings. In a report published in 1970, The Viet Cong Strategy of Terror, the U.S. Information Agency analyst Douglas Pike wrote that at least half of the bodies unearthed in Hue revealed clear evidence of “atrocity killings: to include hands wired behind backs, rags stuffed in mouths, bodies contorted but without wounds (indicating burial alive).” Pike concluded that the killings were done by local VC cadres and were the result of “a decision rational and justifiable in the Communist mind.”

Remains

of a Vietnamese family killed by North Vietnamese Army soldiers in Hue

city during the Tet Offensive. (Defense Dept. photo)

In 1971, journalist Don Oberdorfer’s book Tet!

revealed vivid eyewitness descriptions of what unfolded when the VC

took control of the city. Stephen Miller, a 28-year-old American Foreign

Service Officer with the U.S. Information Service, was in the home of

Vietnamese friends when he was taken away by the VC. They led him to a

field behind a Catholic seminary, bound his arms and then executed him.

German doctors Raimund Discher, Alois Alteköster, and Horst-Günther

Krainick and his wife, all of whom taught at the local medical school,

thought they would be safe as foreign aid workers, but the VC came and

took them away. Their bodies were later found dumped in a shallow grave

in a nearby field. Similarly, two French priests, Fathers Urbain and

Guy, were seen led away. Urbain’s body was later found, bound hand and

foot, where he had been buried alive. Guy’s body, with a bullet in the

back of his head, was found in the same grave with Urbain and 18 others.

Witnesses reported seeing Vietnamese priest Buu Dong, who had

ministered to both sides and even had a photograph of Ho Chi Minh

hanging in his room, being taken away. His body was found 22 months

later in a shallow grave along with the remains of 300 other victims.Making the Viet Cong list of “reactionaries” for working as a part-time janitor at the government information office, Pham Van Tuong was hiding with his family when the VC came for him. When he emerged with his 3-year-old daughter, 5-year-old son and two nephews, the Viet Cong immediately gunned them all down, leaving the bodies in the street for the rest of the family to see.

On the fifth day of the occupation, the Viet Cong went to Phu Cam Cathedral, where they had gathered some 400 men and boys. Some had been on the enemy’s list, some were of military age and some just looked prosperous. They were seen being led away to the south by the VC cadres. It was apparently this group whose remains were later found in the Da Mai Creek bed.

Omar Eby’s book A House in Hue, published in 1968, relates the account of a group of Mennonite aid workers who were trapped in their house during the Communist occupation of the city. The Mennonites told Eby that they saw several Americans, one an agriculturist from the U.S. Agency for International Development, being led away by VC cadre with their arms tied behind their backs. They too were later found executed.

Several writers, including Gunther Lewy in his America in Vietnam, published in 1980, and Peter Macdonald, author of the 1993 book Giap, cite a captured enemy document stating that during the occupation of the city the Communists “eliminated 1,892 administrative personnel, 38 policemen, 790 tyrants.”

Truong Nhu Tang, author of A Vietcong Memoir, published in 1985, tells of a conversation about Hue he had with one of his Viet Cong comrades that acknowledges that atrocities occurred, but his account differs in terms of motivation for the killings. He wrote that a close friend told him that “Discipline in Hue had been seriously inadequate….Fanatic young soldiers had indiscriminately shot people, and angry local citizens who supported the revolution had on various occasions taken justice into their own hands….It had simply been one of those terrible spontaneous tragedies that inevitably accompany war.”

Not everyone agrees that a massacre occurred at Hue, or at least one as described by Pike, Oberdorfer and others. In an article in the June 24, 1974, issue of Indochina Chronicle titled “The 1968 ‘Hue Massacre,’” political scientist D. Gareth Porter called the massacre one of the “enduring myths of the Second Indochina War.” He asserted that Douglas Pike was a “media manipulator par excellence,” working in collusion with the ARVN 10th Political Warfare Battalion to manufacture the story of the massacre at the direction of Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker. While acknowledging that some executions occurred, Porter contended that the killings were not part of any overall plan. Additionally, he claimed that Pike overestimated the number of those killed by the VC cadres and that “thousands” of civilians killed in Hue “were in fact victims of American air power and of the ground fighting that raged in the hamlets, rather than NLF [National Liberation Front] execution.” Moreover, Porter claimed that teams of Saigon government assassins fanned out across the city with their own list of targets, eliminating NLF sympathizers. His conclusion: “The official story of an indiscriminate slaughter of those who were considered to be unsympathetic to the NLF is a complete fabrication.”

Regardless of the actual circumstances of the

civilian deaths, U.S. and South Vietnamese authorities trumpeted the

killings as an object lesson in Communist immorality and a foretaste of

atrocities ahead.

The passage of time did not quell the controversy. In her 1991 book The Vietnam Wars,

historian Marilyn B. Young disputes the “official” figures of

executions at Hue. While acknowledging that there were executions, she

cites freelance journalist Len Ackland, who was at Hue, who estimated

the number to be somewhere between 300 and 400. Attempting “to

understand” what happened at Hue, Young explained that the task of the

NLF was to destroy the government administration of the city,

establishing in its place a “revolutionary administration.” How that

justifies the execution of any civilians, regardless of the number, is

unclear.In his 2002 memoir, From Enemy to Friend, former NVA Colonel Bui Tin shared his insights into the Vietnam War and its aftermath. Present at the defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu and once a guard for Ho Chi Minh, Tin served as a frontline commander who, on April 25, 1975, rode a tank onto the Presidential Palace grounds in Saigon to accept the South Vietnamese surrender. About Hue, Tin acknowledged that some executions of civilians did occur. However, he contended that under the intensity of the American bombardment, the discipline of the troops broke down. The “units from the north” had been “told that Hue was the stronghold of feudalism, a bed of reactionaries, the breeding ground of Can Lao Party loyalists who remained true to the memory of former South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem and of Nguyen Van Thieu’s Democracy Party.” Tin explained that more than 10,000 prisoners were taken at Hue, with the most important of them sent north. When the Marines launched their counterattack to retake the city, the Communist troops were instructed to move the prisoners with the retreating troops. According to Tin, in the “panic of retreat,” some of the company and battalion commanders shot their prisoners “to ensure the safety of the retreat.”

Official Vietnamese military histories cast additional light on Hue. The translation of the official Vietnamese campaign study of the Tet Offensive in the Thua Thien–Hue area acknowledges that Viet Cong cadre “hunted down and captured tyrants and Republic of Vietnam military and government personnel” and that “many nests of tyrants and reactionaries…were killed.” Hundreds of others “who owed blood debts were executed.” Yet another official history, The Tri-Thien-Hue Battlefield During the Victorious Resistance War Against the Americans to Save the Nation, acknowledged widespread killings but maintained they were done at the hands of civilians who armed themselves and “rose up in a flood-tide, killing enemy thugs, eliminating traitors, and hunting down the enemy.…The people captured and punished many reactionaries, enemy thugs, and enemy secret agents.”

Regardless of the actual circumstances of the civilian deaths in Hue, U.S. and South Vietnamese authorities trumpeted the killings as an object lesson in Communist immorality and a foretaste of the atrocities ahead—should the Communists triumph in South Vietnam.

We may never know what really happened at Hue, but it is clear that mass executions did occur and that reports of the massacre there had a significant impact on South Vietnamese and American attitudes for many years after the Tet Offensive. The perception that a bloodbath like the one that occurred at Hue would follow any takeover by the North Vietnamese cast a long shadow and significantly contributed to the abject panic that seized South Vietnam when the North Vietnamese launched their final offensive in 1975—and this panic resulted in the disintegration and defeat of the South Vietnamese armed forces, the fall of Saigon and, ultimately, the demise of the Republic of Vietnam as a sovereign nation.

Vietnam veteran James Willbanks is the director of the Department of Military History, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, and is the author of several books, including The Tet Offensive: A Concise History and Abandoning Vietnam.

(An

Excerpt from the Viet Cong Strategy of Terror,

by

Mr. Douglas Pike, p. 23-39)

(In

Memory of the 7,600 civilians murdered in Hue by Vietnamese communists)

visitors since 8/16/2002

The city of Hue is

one of the saddest cities of our earth, not simply because of what happened

there in February 1968, unthinkable as that was. It is a silent rebuke

to all of us, inheritors of 40 centuries of civilization, who in our century

have allowed collectivist politics-abstractions all-to corrupt us into

the worst of the modern sins, indifference to inhumanity. What happened

in Hue should give pause to every remaining civilized person on this planet.

It should be inscribed, so as not to be forgotten, along with the record

of other terrible visitations of man's inhumanity to man which stud the

history of the human race. Hue is another demonstration of what man can

bring himself to do when he fixes no limits on political action and pursues

incautiously the dream of social perfectibility.

What happened in

Hue, physically, can be described with a few quick statistics. A Communist

force which eventually reached 12,000 invaded the city the night of the

new moon marking the new lunar year, January 30, 1968. It stayed for 26

days and then was driven out by military action. In the wake of this Tet

offensive, 5,800 Hue civilians were dead or missing. It is now known that

most of them are dead. The bodies of most have since been found in single

and mass graves throughout Thua Thien Province which surrounds this cultural

capital of Vietnam.

Such are the skeletal

facts, the important statistics. Such is what the incurious word knows

any thing at all about Hue, for this is what was written, modestly by the

word's press. Apparently it made no impact on the world's mind or conscience.

For there was no agonized outcry. No demonstration at North Vietnamese

embassies around the world. In a tone beyond bitterness, the people there

will tell you that the world does not know what happened in Hue or, if

it does, does not care.

The Battle

The Battle of Hue

was part of the Communist Winter-Spring campaign of 1967-68. The entire

campaign was divided into three phases: Phase I came in October, November,

and December of 1967 and entailed "coordinated fighting methods," that

is, fairly large, set-piece battles against important fixed installations

or allied concentrations. The battles of Loc Ninh in Binh Long Province,

Dak To in Kontum Province, and Con Tien in Quang Tri Province, all three

in the mountainous interior of South Vietnam near the Cambodian and Lao

borders, were typical and, in fact, major elements in

Phase I.

Phase II came

in January, February, and March of 1968 and involved great use of "independent

fighting methods," that is, large numbers of attacks by fairly small units,

simultaneously, over a vast geographic area and using the most refined

and advanced techniques of guerrilla war. Whereas Phase I was fought chiefly

with North Vietnamese Regular (PAVN) troops (at that time some 55,000 were

in the South), Phase II was fought mainly with Southern Communist (PLAF)

troops. The crescendo of Phase II was the Tet offensive in which 70,000

troops attacked 32 of South Vietnam's largest population centres, including

the city of Hue.

Phase III,

in April, May, and June of 1968, originally was to have combined the independent

and coordinated fighting methods, culminating in a great fixed battle somewhere.

This was what captured documents guardedly referred to as the "second wave".

Possibly it was to have been Khe Sanh, the U.S. Marine base in the far

northern corner of South Vietnam. Or perhaps it was to have been Hue. There

was no second wave chiefly because events in Phases I and II did not develop

as expected. Still, the war reached its bloodiest tempo in eight years

then, during the period from the Battle of Hue in February until the lifting

of the siege of Khe Sanh in late summer.

American losses

during those three months averaged nearly 500 killed per week; the

South Vietnamese (GVN) losses were double that rate; and the PAVN-PLAF

losses were nearly eight times the American loss rate. In the Winter-Spring

Campaign, the Communists began with about 195,000 PLAF main force and PAVN

troops. During the nine months they lost (killed or permanently disabled)

about 85,000 men.

The Winter-Spring

Campaign was an all-out Communist bid to break the back of the South Vietnamese

armed forces and drive the government, along with the Allied forces, into

defensive city enclaves. Strictly speaking, the Battle of Hue was part

of Phase I rather than Phase II since it employed "co-ordinated fighting

methods" and involved North Vietnamese troops rather than southern guerrillas.

It was fought, on the Communist side, largely by two veteran North Vietnamese

army divisions: The Fifth 324-B, augmented by main forces battalions and

some guerrilla units along with some 150 local civilian commissars and

cadres.

Briefly the Battle

of Hue consisted of these major developments: The initial Communist assault,

chiefly by the 800th and 802nd battalions, had the force and momentum to

carry it across Hue. By dawn of the first day the Communists controlled

all the city except the headquarters of the First ARVN Division and the

compound housing American military advisors. The Vietnamese and Americans

moved up reinforcements with orders to reach the two holdouts and strengthen

them. The Communists moved up another battalion, the 804th, with orders

to intercept the reinforcement forces. This failed, the two points were

reinforced and never again seriously threatened.

The battle then took

on the aspects of a siege. The Communists were in the Citadel and on the

western edge of the city. The Vietnamese and Americans on the other three

sides, including that portion of Hue south of the river, determined to

drive them out, hoping initially to do so with artillery fire and air strikes.

But the Citadel was well built and soon it became apparent that if the

Communists' orders were to hold, they could be expelled only by city warfare,

fighting house by house and block by block, a slow and costly form of combat.

The order was given.

By the third week

of February the encirclement of the Citadel was well under way and Vietnamese

troops and American Marines were advancing yard by yard through the Citadel.

On the morning of February 24, Vietnamese First Division soldiers tore

down the Communist flag that had flown for 24 days over the outer wall

and hoisted their own. The battle was won, although sporadic fighting would

continue outside the city. Some 2,500 Communists died during the battle

and another 2,500 would die as Communists elements were pursued beyond

Hue. Allied dead were set at 357.

The Finds

In the chaos that

existed following the battle, the first order of civilian business was

emergency relief, in the form of food shipments, prevention of epidemics,

emergency medical care, etc. Then came the home rebuilding effort. Only

later did Hue begin to tabulate its casualties. No true post-attack census

has yet been taken. In March local officials reported that 1,900

civilians were hospitalized with war wounds

and they estimated that some 5,800 persons

were unaccounted for.

The first

discovery of Communist victims came in the Gia Hoi High School yard, on

February 26 ; eventually 170 bodies were

recovered.

In the next few months

18

additional grave sites were found, the

largest of which were Tang Quang Tu Pagoda (67 victims), Bai Dau (77),

Cho Thong area (an estimated 100), the imperial tombs area (201), Thien

Ham (approximately 200), and Dong Gi (approximately 100). In all, almost

1,200

bodies were found in hastily dug, poorly concealed graves.

At least half

of these showed clear evidence of atrocity

killings: hands wired behind backs, rags stuffed

in mouths, bodies contorted but without wounds (indicating burial alive).

The other nearly 600 bore wound marks but there was no way of determining

whether they died by firing squad or incidental to the battle.

The second major

group of finds was discovered in the first seven months of 1969 in Phu

Thu district-the Sand Dune Finds and Le Xa Tay-and Huong Thuy district-Xuan

Hoa-Van Duong-in late March and April. Additional grave sites were found

in Vinh Loc district in May and in Nam Hoa district in July. The largest

of this group were

the Sand Dune Finds

in

the three sites of Vinh Luu, Le Xa Dong and Xuan 0 located in rolling,

grasstufted sand dune country near the South China Sea. Separated by salt-marsh

valleys, these dunes were ideal for graves. Over

800 bodies were uncovered in the dunes.

In the Sand Dune

Find, the pattern had been to

tie victims

together in groups of 10 or 20, line them

up in front of a trench dug by local corvee labour and cut

them down with submachine gun (a favourite

local souvenir is a spent Russian machine gun shell taken from a grave).

Frequently the dead were buried in layers of three and four, which makes

identification particularly difficult.

In Nam Hoa district

came the third, or Da Mai Creek Find, which also has been called the Phu

Cam death march, made on September 19, 1969. Three Communist defectors

told intelligence officers of the 101st Airborne Brigade that they had

witnessed the killing of several hundred people at Da Mai Creek, about

10 miles south of Hue, in February of 1968. The area is wild, unpopulated,

virtually inaccessible. The Brigade sent in a search party, which reported

that the stream contained a large number of human bones.

By piecing together

bits of information, it was determined that this is what happened at Da

Mai Creek: On the fifth day of Tet in the Phu Cam section of Hue, where

some three-quarters of the City's 40,000 Roman Catholics lived, a large

number of people had taken sanctuary from the battle in a local church,

a common method in Vietnam of escaping war. Many in the building were not

in fact Catholic.

A Communist political

commissar arrived at the church and ordered out about 400 people, some

by name and some apparently because of their appearance (prosperous looking

and middle-aged businessmen, for example). He said they were going to the

"liberated area" for three days of indoctrination, after which each could

return home.

They were marched

nine kilometres south to a pagoda where the Communists had established

a headquarters. There 20 were called out from

the group, assembled before a drumhead court, tried, found guilty, executed

and buried in the pagoda yard. The remainder

were taken across the river and turned over to a local Communist unit in

an exchange that even involved banding the political commissar a receipt.

It is probable that the commissar intended that their prisoners should

be re-educated and returned, but with the turnover, matters passed from

his control.

During the next several

days, exactly how many is not known, both captive and captor wandered the

countryside. At some point the local Communists

decided to eliminate witnesses: Their

captives were led through six kilometres of some of the most rugged terrain

in Central Vietnam, to Da Mai Creek. There they were shot or brained and

their bodies left to wash in the running stream. The 101st Airborne Brigade

burial detail found it impossible to reach the creek overland, roads being

non-existent or impassable. The creek's foliage is what in Vietnam is called

double-canopy, that is, two layers, one consisting of brush and trees close

to the ground, and the second of tall trees whose branches spread out high

above. Beneath is permanent twilight. Brigade engineers spent two days

blasting a hole through the double-canopy by exploding dynamite dangled

on long wires beneath their hovering helicopters. This cleared a landing

pad for helicopter hearses. Quite clearly this was a spot where death could

be easily hidden even without burial.

The Da Mai Creek

bed, for nearly a hundred yards up the ravine, yielded skulls, skeletons

and pieces of human bones. The dead had been left above ground (for the

animists among them, this meant their souls would wander the lonely earth

forever, since such is the fate of the unburied dead), and 20 months in

the running stream had left bones clean and white.

Local authorities

later released a list of 428 names of personswhom

they said had been positively identified from the creek bed remains.

The Communists' rationale for their excesses was elimination of "traitors

to the revolution." The list of 428 victims breaks down as follows: 25

per cent military: two officers, the rest NCO's and enlisted men; 25 per

cent students; 50 per cent civil servants, village and hamlet officials,

service personnel of various categories, and ordinary workers.

The fourth or Phu

Thu Salt Flat Finds came in November, 1969, near the fishing village of

Luong Vien some ten miles east of Hue, another desolate region. Government

troops early in the month began an intensive effort to clear the area of

remnants of the local Communist organization. People of Luong Vien, population

700, who had remained silent in the presence of troops for 20 months apparently

felt secure enough from Communist revenge to break silence and lead officials

to the find. Based on descriptions from villagers whose memories are not

always clear, local officials estimate the number

of bodies at Phu Thu to be at least 300 and possibly 1,000.

The story remains

uncompleted. If the estimates by Hue officials are even approximately correct,

nearly 2,000 people are still missing. Re-capitulation of the dead and

missing.

Mass grave of Communists victims was uncovered in Khe Da Mai (Hue) - Patrick J. Honey Collection - Vietnam Center and Archive

After the battle, the Goverment of South Viet Nam's total estimated civilian casualties resulting from Battle of Hue 7,600:

| Wounded (hospitalized or outpatients) with injures attributable to warfare Estimated civilian deaths due to accident of battle First finds-bodies discovered immediately post battle, 1968 Second finds, including Sand Dune finds, March-July, 1969 (est.) Third find, Da Mai Creek find (Nam Hoa district) September, 1969 Fourth Finds-Phu Thu Salt Flat find, November, 1969 (est.) Miscellaneous finds during 1969 (approximate) Total yet unaccounted for Total casualty and wounded in Hue | 1900 844 1173 809 428 300 200 1946 ~ 7,600 |

[1] SEATO: South East Asia Organization. [2] PAVN: People's Army of Vietnam, soldiers of North Vietnam Army serving in the South, number currently 105,000. [3] PLAF: People's Liberation Armed Force, Formerly called the National Liberation Front Army.

Communist Rationale

The killing in Hue

that added up to the Hue Massacre far exceeded in numbers any atrocity

by the Communists previously in South Vietnam. The difference was not only

one in degree but one in kind. The character of the terror that emerges

from an examination of Hue is quite distinct from Communist terror acts

elsewhere, frequent or brutal as they may have been. The terror in Hue

was not a morale building act-the quick blow deep into the enemy's lair

which proves enemy vulnerability and the guerrilla's omnipotence and which

is quite different from gunning down civilians in areas under guerrilla

control. Nor was it terror to advertise the cause. Nor to disorient and

psychologically isolate the individual, since the vast majority of the

killings were done secretly. Nor, beyond the blacklist killings, was it

terror to eliminate opposing forces. Hue did not follow the pattern of

terror to provoke governmental over-response since it resulted in only

what might have been anticipated-government assistance. There were elements

of each objective, true, but none serves to explain the widespread and

diverse pattern of death meted out by the Communists.

What is offered here

is a hypothesis which will suggest logic and system behind what appears

to be simple, random slaughter. Before dealing with it, let us consider

three facts which constantly reassert themselves to a Hue visitor seeking

to discover what exactly happened there and, more importantly, exactly

why it happened. All three fly in the face of common sense and contradict

to a degree what has been written. Yet, in talking to all sources-province

chief, police chief, American advisor, eye witness, captured prisoner,

hoi chanh (defector) or those few who miraculously escaped a death scene-the

three facts emerge again and again.

The first fact, and

perhaps the most important, is that despite contrary appearances virtually

no Communist killing was due to rage, frustration, or panic during the

Communist withdrawal at the end. Such explanations are frequently heard,

but they fail to hold up under scrutiny. Quite the contrary, to trace back

any single killing is to discover that almost without exception it was

the result of a decision rational and justifiable in the Communist mind.

In fact, most killings were, from the Communist calculation, imperative.

The second fact is

that, as far as can be determined, virtually all killings were done by

local Communist cadres and not by the ARVN troops or Northerners or other

outside Communists. Some 12,000 ARVN troops fought the battle of Hue and

killed civilians in the process but this was incidental to their military

effort. Most of the 150 Communist civilian cadres operating within the

city were local, that is from the Thua Thien province area. They were the

ones who issued the death orders.

Whether they acted

on instructions from higher headquarters (and the Communist organizational

system is such that one must assume they did), and, if so, what exactly

those orders were, no one yet knows for sure. The third fact is that beyond

"example" executions of prominent "tyrants", most of the killings were

done secretly with extraordinary effort made to hide the bodies. Most outsiders

have a mental picture of Hue as a place of public executions and prominent

mass burial mounds of fresh-turned earth. Only in the early days were there

well-publicized executions and these were relatively few. The burial sites

in the city were easily discovered because it is difficult to create a

graveyard in a densely populated area without someone noticing it. All

the other finds were well hidden, all in terrain lending itself to concealment,

probably the reason the sites were chosen in the first place.

A body in the sand

dunes is as difficult to find as a seashell pushed deep into a sandy beach

over which a wave has washed. Da Mai Creek is in the remotest part of the

province and must have required great exertion by the Communists to lead

their victims there. Had not the three hoi chanh led searchers to the wild

uninhabited spot the bodies might well remain undiscovered to this day.

A visit to all sites leaves one with the impression that the Communists

made a major effort to hide their deeds. The hypothesis offered here connects

and fixes in time the Communist assessment of their prospects for staying

in Hue with the kind of death order issued. It seems clear from sifting

evidence that they had no single unchanging assessment with regard to themselves

and their future in Hue, but rather that changing situations during the

course of the battle altered their prospects and their intentions.

It also seems equally

clear from the evidence that there was no single Communist policy on death

orders; instead the kind of death order issued changed during the course

of the battle. The correlation between these two is high and divides into

three phases. The hypothesis therefore is that as Communist plans during

the Battle of Hue changed so did the nature of the death orders issued.

This conclusion is based on overt Communist statements, testimony by prisoners1

and hoi chanh, accounts of eyewitnesses, captured documents and the internal

logic of the Communist situation.

Thinking in Phase

I was well expressed in a Communist Party of South Vietnam (PRP) resolution

issued to cadres on the eve of the offensive: Be sure that the liberated

... cities are successfully consolidated. Quickly activate armed and political

units, establish administrative organs at all echelons, promote (civilian)

defence and combat support activities, get the people to establish an air

defence system and generally motivate them to be ready to act against the

enemy when he counterattacks..."

This was the limited

view at the start - held momentarily. Subsequent developments in Hue were

reported in different terms. Hanoi Radio on February 4 said: "After one

hour's fighting the Revolutionary Armed Forces occupied the residence of

the puppet provincial governor (in Hue), the prison and the offices of

the puppet administration... The Revolutionary Armed Forces punished most

cruel agents of the enemy and seized control of the streets... rounded

up and punished dozen of cruel agents and caused the enemy organs of control

and oppression to crumble...

During the brief

stay in Hue, the civilian cadres, accompanied by execution squads, were

to round up and execute key individuals whose elimination would greatly

weaken the government's administrative apparatus following Communist withdrawal.

This was the blacklist period, the time of the drumhead court. Cadres with

lists of names and addresses on clipboards appeared and called into kangaroo

court various "enemies of the Revolution."

Their trials were

public, usually in the court-yard of a temporary Communist headquarters.

The trials lasted about ten minutes each and there are no known not-guilty

verdicts. Punishment, invariably execution, was meted out immediately.

Bodies were either hastily buried or turned over to relatives. Singled

out for this treatment were civil servants, especially those involved in

security or police affairs, military officers and some non-commissioned

officers, plus selected non-official but natural leaders of the community,

chiefly educators and religionists.

With the exception

of a particularly venomous attack on Hue intellectuals, the Phase I pattern

was standard operating procedure for Communists in Vietnam. It was the

sort of thing that had been going on systematically in the villages for

ten years. Permanent blacklists, prepared by zonal or inter-zone party

headquarters have long existed for use throughout the country, whenever

an opportunity presents itself.

However, not all

the people named in the lists used in Hue were liquidated. There were a

large number of people who obviously were listed, who stayed in the city

throughout the battle, but escaped. Throughout the 24-day period the Communist

cadres were busy hunting down persons on their blacklists, but after a

few days their major efforts were turned into a new channel.

Hue: Phase II

In the first few

days, the Tet offensive affairs progressed so well for the Communists in

Hue (although not to the south, where party chiefs received some rather

grim evaluations from cadres in the midst of the offensive in the Mekong

Delta) that for a brief euphoric moment they believed they could hold the

city. Probably the assessment that the Communists were in Hue to stay was

not shared at the higher echelons, but it was widespread in Hue and at

the Thua Thien provincial level. One intercepted Communist message, apparently

written on February 2, exhorted cadres in Hue to hold fast, declaring;

"A new era, a real revolutionary period has begun (because of our Hue victories)

and we need only to make swift assault (in Hue) to secure our target and

gain total victory."

The Hanoi official

party newspaper, Nhan Dan, echoed the theme: "Like a thunderbolt, a general

offensive has been hurled against the U.S. and the puppets... The U.S.-puppet

machine has been duly punished. The puppet administrative organs... have

suddenly collapsed. The Thieu-Ky administration cannot escape from complete

collapse. The puppet troops have become extremely weak and cannot avoid

being completely exterminated."

Of course, some of

this verbiage is simply exhortation to the faithful, and, as is always

the case in reading Communist output, it is most difficult to distinguish

between belief and wish. But testimony from prisoners and hoi chanh, as

well as intercepted battle messages, indicate that both rank and file and

cadres believed for a few days they were permanently in Hue, and they acted

accordingly.

Among their acts

was to extend the death order and launch what in effect was a period of

social reconstruction, Communist style. Orders went out, apparently from

the provincial level of the party, to round up what one prisoner termed

"social negatives," that is, those individuals or members of groups who

represented potential danger or liability in the new social order. This

was quite impersonal, not a blacklist of names but a blacklist of titles

and positions held in the old society, directed not against people as such

but against "social units."

As seen earlier in

North Vietnam and in Communist China, the Communists were seeking to break

up the local social order by eliminating leaders and key figures in religious

organizations (Buddhist bonzes, Catholic priests), political parties (four

members of the Central Committee of Vietnam), social movements such as

women's organizations and youth groups, including what otherwise would

be totally inexplicable, the execution of pro-Communist student leaders

from middle and upper class families.

In consonance with

this, killing in some instances was done by family unit. In one well-documented

case during this period a squad with a death order entered the home of

a prominent community leader and shot him, his wife, his married son and

daughter-in-law, his young unmarried daughter, a male and female servant

and their baby. The family cat was strangled; the family dog was clubbed

to death; the goldfish scooped out of the fish-bowl and tossed on the floor.

When the Communists left, no life remained in the house. A "social unit"

had been eliminated.

Phase II also

saw an intensive effort to eliminate intellectuals, who are perhaps more

numerous in Hue than elsewhere in Vietnam. Surviving Hue intellectuals

explain this in terms of a long-standing Communist hatred of Hue intellectuals,

who were anti-Communist in the worst or most insulting manner: they refused

to take Communism seriously. Hue intellectuals have always been contemptuous

of Communist ideology, brushing it aside as a latecomer to the history

of ideas and not a very significant one at that. Hue, being a bastion of

traditionalism, with its intellectuals steeped in Confucian learning intertwined

with Buddhism, did not, even in the fermenting years of the 1920s, and

1930s, debate the merits of Communism. Hue ignored it. The intellectuals

in the university, for example, in a year's course in political thought

dispense with Marxism-Leninism in a half hour lecture, painting it as a

set of shallow barbarian political slogans with none of the depth and time-tested

reality of Confucian learning, nor any of the splendor and soaring humanism

of Buddhist thought.

Since the Communist,

especially the Communist from Hue, takes his dogma seriously, he can become

demoniac when dismissed by a Confucian as a philosophic ignoramus, or by

a Buddhist as a trivial materialist. Or, worse than being dismissed, ignored

through the years. So with the righteousness of a true believer, he sought

to strike back and eliminate this challenge of indifference. Hue intellectuals

now say the hunt-down in their ranks has taught them a hard lesson, to

take Communism seriously, if not as an idea, at least as a force loose

in their world.

The killings in Phase

II perhaps accounted for 2,000 of the missing. But the worst was not yet

over.

Hue: Phase III

Inevitably, and as

the leadership in Hanoi must have assumed all along, considering the forces

ranged against it, the battle in Hue turned against the Communists. An

intercepted PAVN radio message from the Citadel, February 22, asked for

permission to withdraw. Back came the reply: permission refused, attack

on the 23rd. That attack was made, a last, futile one. On the 24th the

Citadel was taken.

That expulsion was

inevitable was apparent to the Communists for at least the preceding week.

It was then that Phase III began, the cover-the-traces period. Probably

the entire civilian underground apparat in Hue had exposed itself during

Phase II. Those without suspicion rose to proclaim their identity. Typical

is the case of one Hue resident who described his surprise on learning

that his next door neighbour was the leader of a phuong (which made him

10th to 15th ranking Communist civilian in the city), saying in wonder,

"I'd known him for 18 years and never thought he was the least interested

in politics." Such a cadre could not go underground again unless there

was no one around who remembered him.

Hence Phase III,

elimination of witnesses. Probably the largest number of killings came

during this period and for this reason. Those taken for political indoctrination

probably were slated to be returned. But they were local people as were

their captors; names and faces were familiar. So, as the end approached

they became not just a burden but a positive danger. Such undoubtedly was

the case with the group taken from the church at Phu Cam. Or of the 15

high school students whose bodies were found as part of the Phu Thu Salt

Flat find.

Categorization in

a hypothesis such as this is, of course, gross and at best only illustrative.

Things are not that neat in real life. For example, throughout the entire

time the blacklist hunt went on. Also, there was revenge killing by the

Communists in the name of the party, the so-called "revolutionary justice."

And undoubtedly there were personal vendettas, old scores settled by individual

party members.

The official Communist

view of the killing in Hue was contained in a book written and published

in Hanoi: "Actively combining their efforts with those of the PLAF and

population, other self-defence and armed units of the city (of Hue) arrested

and called to surrender the surviving functionaries of the puppet administration

and officers and men of the puppet army who were skulking. Die-hard cruel

agents were punished."

The Communist line

on the Hue killings later at the Paris talks was that it was not the work

of Communists but of "dissident local political parties". However, it should

be noted that Hanoi's Liberation Radio April 26, 1968, criticized the effort

in Hue to recover bodies, saying the victims were only "hooligan lackeys

who had incurred blood debts of the Hue compatriots and who were annihilated

by the Southern armed forces and people in early Spring." This propaganda

line however was soon dropped in favour of the line that it really was

local political groups fighting each other.

......................

(An Excerpt from the Viet Cong Strategy of Terror, Douglas Pike,

p. 23-39)

With sincere gratitude,

we are paying respect to the late Professor/Author Douglas Eugene Pike

of Texas Tech University.

http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/vietnamcenter/general/douglas_pike.htm

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

California's Vietnamese refugees are incensed and claim that the exhibit at the Oakland Art Museum scheduled for 2004 does not give them adequate representation. They are also protesting the firing of a Vietnamese American employee at the museum who spoke out against the exhibit.

The museum received a National Endowment grant for a retrospective exhibit on the Vietnam War and its impact on California. The grant stipulates that the Next Stop Vietnam exhibit should engage in a dialogue with the community, but very little of that has happened, according to Mimi Nguyen, who says she was fired after repeated efforts to call the museum's attention to the cursory representation of Vietnamese voices and experience. Instead, she says, the exhibit focuses on the experience of the U.S. veteran community and does not represent the experience of not only Vietnamese, but other Southeast Asian groups that populate California.

In a letter to the museum's administration which was leaked to Vietnamese language press, Nguyen wrote, "Fifty-eight thousand American GIs died in the war. Some four million Vietnamese perished, and an entire nation collapsed. Shouldn't Vietnamese Californians have equal stake and voice in this exhibit?"

She wrote that initial agreements to interview Vietnamese living in California on their reaction to U.S. troops arriving in Vietnam were retracted and eliminated from the exhibit.

"Thanh was eight when American troops tossed a grenade into his family's bomb shelter. The grenade ruptured his vocal cords and disfigured his face. Duong was eleven when strayed bullets ruptured his spinal cord, leaving him paraplegic; he overcame many obstacles to become an Assistant Professor of Education at UCLA today," she wrote.

She says Vietnamese are portrayed as refugees at the end of the war without struggle, heritage, history and past.

She wonders if the stories were neglected because the public cannot handle the realities of the Vietnam War. "Or are we uncomfortable with the truth because Vietnam reminds Americans of our discomforting role in transforming the Persian Gulf? Wouldn't this reality shake people out of their comfort zone to deal with 'collateral damage' in Iraq and Afghanistan?"

The exhibit will highlight the widely known My Lai massacre where American forces attacked a Vietnamese village, but she says other atrocities like the Hue Massacre deserve to be uncovered. The memories still haunt survivors living in California. During the Hue massacre, some 4,000 students, professors, doctors, government officials and their families were buried alive by the Vietnamese Communist soldiers in mass graves.

Some 21 U.S. veterans were interviewed for the exhibit compared to only one or two South Vietnamese soldiers, she wrote. "Over one million South Vietnamese men were under arms, and many are now Californians whose stories deserve our attention and a better history than the United States allows."

She says Vietnamese play a valuable part of the California landscape and deserve an exhibit that speaks to them. "Refugees include sons, daughters, nieces, nephews and grandchildren of former South Vietnamese officials, who are transforming California and the nation as well. Vietnamese engineers and assembly line laborers helped build Silicon Valley, the engine of California's economy that was generating wealth and income, making California the richest state in the country."

The largest overseas Vietnamese population resides in California, numbering some half a million, and yet their views are not well represented, Nguyen says. The Vietnamese community, from Oakland to San Jose to Orange County, plan to circulate petitions and protest the museum's actions. Last week the deputy mayor of Garden Grove held a townhall meeting on the issue. Other Southeast Asian groups as well as a cross-cultural mix of immigrant and advocacy groups plan to join the Vietnamese in their protests. They include the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and PUEBLO, a local activist organization.

Compiled by Pueng Vongs CaliToday News Report November 4, 2003

http://vnafmamn.com/fighting/massacre_athue.html

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FIGHTING THE LOST WAR section - vnafmamn.com

"Massacre At Hue" by Gucci (diptych, oils on canvas (56"x 30" & 26"x30"), 1980)

Most people heard of My Lai atrocity, but a few would know of Hue massacre. Today some Hanoi's sympathyzers have even tried to whitewash the war crime by saying the Hue massacre never happened. It sounds just like the neo-nazis saying the Holocaust is a myth. The two following articles will offer you a better perspective (thanks to the recent opening of LIFE photo's archive, we found the original pictures of Hue massacre related photos that were thought ever lost).THE SILENT TEARS IN HUE CITY

In the darkness of the 1968 Tet's Eve, North Vietnamese Communist

Army units conducted a surprise attack at Hue City, while the two sides

were in a truce that had been agreed upon previously. South Vietnamese

Army units defending the city were not in good positions to fight as

they expected that the enemy would abide by their 4-day cease-fire

promise, as they did in the preceding years. On the first day of the new

year - the Year of the Monkey - Hue City streets were filled with NVA

soldiers in baggy olive uniforms and pithy hats.

The communist cadres set up the provisionary authorities. The first thing they did was call all ARVN soldiers, civil servants of all services, political party members, and college students, to report to the "revolutionary people's committee." Those who reported to the communist committee were registered in control books then released with promise of safety.

After a few days, they were called to report again, then all were sent home safe and sound. During three weeks under NVA units' occupation, they were ordered to report to the communist committee three or four times. In the late half of January 1968, the US Marines and the South Vietnamese infantry conducted bloody counterattacks and recaptured the whole city after many days of fierce fighting that forced their enemy to withdraw in several directions.

Meanwhile, those who were called to report the last time to the communist authorities disappeared after the Marines and South Vietnamese Army units liberated Hue. Most of the missing were soldiers in non-combat units and young civilians. No one knew their whereabouts.

In late Feb.1968, from reports of Vietnamese Communist ralliers and POWs, the South Vietnamese local authorities found several mass graves. In each site, hundreds of bodies of the missing were buried. Most were tied to each other by ropes, electric wires or telephone wires. They had been shot or beaten or even stabbed to death. The mass graves shocked the city and the whole country. Almost every family in Hue has at least one relative, close or remote, who was killed or still missing. The latest mass grave found in the front yard of a Phu Thu district elementary school in May 1972, contained some two hundred bodies under the sand. They had been slaughtered during one-month occupation of an NVA unit. Sand left no sign of a mass grave below until a 3rd-grader dug the ground rather deep for a cricket.

Besides more than two thousand persons whose deaths were confirmed after the revelation of the mass graves, the fate of the others, amounted to several thousands, are still unknown.The 1968 massacre in Hue brought a sharp turn in the common attitude toward the war. A great number of the pre-'68 fence sitters, anti-war activists, and even pro-Communist people, took side with the South Vietnamese government after the horrible events. After April 30, 1975 when South Vietnam fell into the hand of the Communist Party, it seems that the number of boat people of Hue origin takes up a greater proportion among the refugees than that from the other areas.

Since April 1975, the Vietnamese Communist regime deliberately moved many families of the 68-massacre victims out of Hue City. People in the city however, still commemorate them every year. Because the people are mingling the rites with Tet celebrations, Communist local authorities have no reason to forbid them.

Most Americans knew well about the My Lai massacre of US Army Lieutenant Calley where from 200 to 350 persons were killed. The '68-massacre in Hue however, has not been covered at the same proportion by the English language media. When a Tet Offensive documentary film by South Vietnamese reporters was shown to the American audience of more than 200 US Army officers in Fort Benning, Ga. in November 1974, almost 90 percent of them hadn't been informed of the facts. Many even said that had they known the savage slaughter at the time, they would have acted differently while serving in Vietnam.

The US Navy has a warship named "Hue City." It is not known how many of her sailors realize that the city she carries as a name suffered so much. Would it be a good idea to have a rite once a year in the Tet season on the "Hue City" for the dead whom the US Marines were fighting for in February 1968?

Animosity should not be handed down to younger generations, but our descendants must be taught the truth. War crimes must not be forgotten, and history is not written by one-sided writers.

Reposted from VietQuoc Homepage

The communist cadres set up the provisionary authorities. The first thing they did was call all ARVN soldiers, civil servants of all services, political party members, and college students, to report to the "revolutionary people's committee." Those who reported to the communist committee were registered in control books then released with promise of safety.

After a few days, they were called to report again, then all were sent home safe and sound. During three weeks under NVA units' occupation, they were ordered to report to the communist committee three or four times. In the late half of January 1968, the US Marines and the South Vietnamese infantry conducted bloody counterattacks and recaptured the whole city after many days of fierce fighting that forced their enemy to withdraw in several directions.

Meanwhile, those who were called to report the last time to the communist authorities disappeared after the Marines and South Vietnamese Army units liberated Hue. Most of the missing were soldiers in non-combat units and young civilians. No one knew their whereabouts.

In late Feb.1968, from reports of Vietnamese Communist ralliers and POWs, the South Vietnamese local authorities found several mass graves. In each site, hundreds of bodies of the missing were buried. Most were tied to each other by ropes, electric wires or telephone wires. They had been shot or beaten or even stabbed to death. The mass graves shocked the city and the whole country. Almost every family in Hue has at least one relative, close or remote, who was killed or still missing. The latest mass grave found in the front yard of a Phu Thu district elementary school in May 1972, contained some two hundred bodies under the sand. They had been slaughtered during one-month occupation of an NVA unit. Sand left no sign of a mass grave below until a 3rd-grader dug the ground rather deep for a cricket.

Besides more than two thousand persons whose deaths were confirmed after the revelation of the mass graves, the fate of the others, amounted to several thousands, are still unknown.The 1968 massacre in Hue brought a sharp turn in the common attitude toward the war. A great number of the pre-'68 fence sitters, anti-war activists, and even pro-Communist people, took side with the South Vietnamese government after the horrible events. After April 30, 1975 when South Vietnam fell into the hand of the Communist Party, it seems that the number of boat people of Hue origin takes up a greater proportion among the refugees than that from the other areas.

Since April 1975, the Vietnamese Communist regime deliberately moved many families of the 68-massacre victims out of Hue City. People in the city however, still commemorate them every year. Because the people are mingling the rites with Tet celebrations, Communist local authorities have no reason to forbid them.

Most Americans knew well about the My Lai massacre of US Army Lieutenant Calley where from 200 to 350 persons were killed. The '68-massacre in Hue however, has not been covered at the same proportion by the English language media. When a Tet Offensive documentary film by South Vietnamese reporters was shown to the American audience of more than 200 US Army officers in Fort Benning, Ga. in November 1974, almost 90 percent of them hadn't been informed of the facts. Many even said that had they known the savage slaughter at the time, they would have acted differently while serving in Vietnam.

The US Navy has a warship named "Hue City." It is not known how many of her sailors realize that the city she carries as a name suffered so much. Would it be a good idea to have a rite once a year in the Tet season on the "Hue City" for the dead whom the US Marines were fighting for in February 1968?

Animosity should not be handed down to younger generations, but our descendants must be taught the truth. War crimes must not be forgotten, and history is not written by one-sided writers.

Reposted from VietQuoc Homepage

An other writing relates a bit about Hue Massacre,

but more interestingly it offers an insightful perspective on how the

"academic intellectuals" still biased against South Vietnamese when

showcasing the Vietnam war. Please continue the article below.

A Smithsonian exhibit of the World War II bomber the Enola Gay is

being criticized for its failure to mention the destruction the plane

caused when it dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. Vietnamese Americans in

California say an upcoming Oakland exhibit on the Vietnam War commits a

similar crime.California's Vietnamese refugees are incensed and claim that the exhibit at the Oakland Art Museum scheduled for 2004 does not give them adequate representation. They are also protesting the firing of a Vietnamese American employee at the museum who spoke out against the exhibit.

The museum received a National Endowment grant for a retrospective exhibit on the Vietnam War and its impact on California. The grant stipulates that the Next Stop Vietnam exhibit should engage in a dialogue with the community, but very little of that has happened, according to Mimi Nguyen, who says she was fired after repeated efforts to call the museum's attention to the cursory representation of Vietnamese voices and experience. Instead, she says, the exhibit focuses on the experience of the U.S. veteran community and does not represent the experience of not only Vietnamese, but other Southeast Asian groups that populate California.

In a letter to the museum's administration which was leaked to Vietnamese language press, Nguyen wrote, "Fifty-eight thousand American GIs died in the war. Some four million Vietnamese perished, and an entire nation collapsed. Shouldn't Vietnamese Californians have equal stake and voice in this exhibit?"

She wrote that initial agreements to interview Vietnamese living in California on their reaction to U.S. troops arriving in Vietnam were retracted and eliminated from the exhibit.

"Thanh was eight when American troops tossed a grenade into his family's bomb shelter. The grenade ruptured his vocal cords and disfigured his face. Duong was eleven when strayed bullets ruptured his spinal cord, leaving him paraplegic; he overcame many obstacles to become an Assistant Professor of Education at UCLA today," she wrote.

She says Vietnamese are portrayed as refugees at the end of the war without struggle, heritage, history and past.

She wonders if the stories were neglected because the public cannot handle the realities of the Vietnam War. "Or are we uncomfortable with the truth because Vietnam reminds Americans of our discomforting role in transforming the Persian Gulf? Wouldn't this reality shake people out of their comfort zone to deal with 'collateral damage' in Iraq and Afghanistan?"

The exhibit will highlight the widely known My Lai massacre where American forces attacked a Vietnamese village, but she says other atrocities like the Hue Massacre deserve to be uncovered. The memories still haunt survivors living in California. During the Hue massacre, some 4,000 students, professors, doctors, government officials and their families were buried alive by the Vietnamese Communist soldiers in mass graves.

Some 21 U.S. veterans were interviewed for the exhibit compared to only one or two South Vietnamese soldiers, she wrote. "Over one million South Vietnamese men were under arms, and many are now Californians whose stories deserve our attention and a better history than the United States allows."

She says Vietnamese play a valuable part of the California landscape and deserve an exhibit that speaks to them. "Refugees include sons, daughters, nieces, nephews and grandchildren of former South Vietnamese officials, who are transforming California and the nation as well. Vietnamese engineers and assembly line laborers helped build Silicon Valley, the engine of California's economy that was generating wealth and income, making California the richest state in the country."

The largest overseas Vietnamese population resides in California, numbering some half a million, and yet their views are not well represented, Nguyen says. The Vietnamese community, from Oakland to San Jose to Orange County, plan to circulate petitions and protest the museum's actions. Last week the deputy mayor of Garden Grove held a townhall meeting on the issue. Other Southeast Asian groups as well as a cross-cultural mix of immigrant and advocacy groups plan to join the Vietnamese in their protests. They include the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and PUEBLO, a local activist organization.

Compiled by Pueng Vongs CaliToday News Report November 4, 2003

http://vnafmamn.com/fighting/massacre_athue.html

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét